Getting Started¶

Quick Start¶

This guide is intended for running Singularity on a computer where you have root (administrative) privileges. If you are learning about Singularity on a system where you lack root privileges, you can still complete the steps that do not require the sudo command. If you need to request an installation on your shared resource, check out our requesting an installation help page for information to send to your system administrator.

Installation¶

git clone https://github.com/singularityware/singularity.git

cd singularity

./autogen.sh

./configure --prefix=/usr/local

make

sudo make install

Singularity must be installed as root to function properly.

Overview of the Singularity Interface¶

$ singularity --help

USAGE: singularity [global options...] <command> [command options...] ...

GLOBAL OPTIONS:

-d|--debug Print debugging information

-h|--help Display usage summary

-s|--silent Only print errors

-q|--quiet Suppress all normal output

--version Show application version

-v|--verbose Increase verbosity +1

-x|--sh-debug Print shell wrapper debugging information

GENERAL COMMANDS:

help Show additional help for a command or container

selftest Run some self tests for singularity install

CONTAINER USAGE COMMANDS:

exec Execute a command within container

run Launch a runscript within container

shell Run a Bourne shell within container

test Launch a testscript within container

CONTAINER MANAGEMENT COMMANDS:

apps List available apps within a container

bootstrap *Deprecated* use build instead

build Build a new Singularity container

check Perform container lint checks

inspect Display a container's metadata

mount Mount a Singularity container image

pull Pull a Singularity/Docker container to $PWD

COMMAND GROUPS:

image Container image command group

instance Persistent instance command group

CONTAINER USAGE OPTIONS:

see singularity help <command>

For any additional help or support visit the Singularity

website: http://singularity.lbl.gov/

$ singularity --debug run shub://GodloveD/lolcow

And to pass the option to the command and run a Singularity image in an isolated manner:

$ singularity run --containall shub://GodloveD/lolcow

To learn more about a specific Singularity command, type one of the following:

$ singularity help <command>

$ singularity --help <command>

$ singularity -h <command>

$ singularity <command> --help

$ singularity <command> -h

$ singularity help container.simg # See the container's help, if provided

$ singularity help --app foo container.simg # See the help for foo, if provided

Download pre-built images¶

You can use the a href=“sec:pull”>pull</a> and a href=”sec:build”>build</a> commands to download pre-built images from an external resource like `Singularity Hub`_ or Docker Hub. When called on a native Singularity images like those provided on Singularity Hub, simply downloads the image file to your system.

$ singularity pull shub://vsoch/hello-world # pull with default name, vsoch-hello-world-master.simg

$ singularity pull --name hello.simg shub://vsoch/hello-world # pull with custom name

$ singularity pull docker://godlovedc/lolcow # with default name

$ singularity pull --name funny.simg docker://godlovedc/lolcow # with custom name

$ singularity build hello-world.simg shub://vsoch/hello-world

$ singularity build lolcow.simg docker://godlovedc/lolcow

Unlike , will convert your image to the latest Singularity image format after downloading it.

is like a “Swiss Army knife” for container creation. In addition to downloading images, you can use to create images from other images or from scratch using a a href=“sec:recipefile”>recipe file</a>. You can also use to convert an image between the 3 major container formats supported by Singularity. We discuss those image formats below in the a href=”sec:buildimagesfromscratch”>Build images from scratch</a> section.

Interact with images¶

Once you have an image, you can interact with it in several ways. For these examples we will use a image that can be downloaded from Singularity Hub like so.

$ singularity pull --name hello-world.simg shub://vsoch/hello-world

The <a href=”#sec:shell”>shell</a> command allows you to spawn a new shell within your container and interact with it as though it were a small virtual machine.

$ singularity shell hello-world.simg

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

# I am the same user inside as outside!

Singularity hello-world.simg:~/Desktop> whoami

vanessa

Singularity hello-world.simg:~/Desktop> id

uid=1000(vanessa) gid=1000(vanessa) groups=1000(vanessa),4(adm),24,27,30(tape),46,113,128,999(input)

also works with the and URIs. This creates an ephemeral container that disappears when the shell is exited.

$ singularity shell shub://vsoch/hello-world

The <a href=”#sec:exec”>exec</a> command allows you to execute a custom command within a container by specifying the image file. For instance, to list the root (/) of our hello-world.simg image, we could do the following:

$ singularity exec hello-world.simg ls /

anaconda-post.log etc lib64 mnt root singularity tmp

bin home lost+found opt run srv usr

dev lib media proc sbin sys var

$ singularity exec shub://singularityhub/ubuntu cat /etc/os-release

Singularity containers contain “a href=”#sec:runscript”>runscripts</a>”. These are user defined scripts that define the actions a container should perform when someone runs it. The runscript can be triggered with the run command, or simply by calling the container as though it were an executable.

$ singularity run hello-world.simg

$ ./hello-world.simg

also works with and URIs. This creates an ephemeral container that runs and then disappears.

$ singularity run shub://GodloveD/lolcow

$ echo "Hello World" > $HOME/hello-kitty.txt

$ singularity exec vsoch-hello-world-master.simg cat $HOME/hello-kitty.txt

Hello World

$ echo "I am your father" >/data/vader.sez

$ ~/sing-dev/bin/singularity exec --bind /data:/mnt hello-world.simg cat /mnt/vader.sez

I am your father

Build images from scratch¶

For more details about the different build options and best practices, read about the <a href=”#sec:singularityflow”>singularity flow</a>.

$ sudo singularity build --sandbox ubuntu/ docker://ubuntu

$ sudo singularity build --writable ubuntu.img docker://ubuntu

$ sudo singularity shell --writable ubuntu.img

$ singularity build new-squashfs sandbox

Bootstrap: shub

From: singularityhub/ubuntu

%runscript

exec echo "The runscript is the containers default runtime command!"

%files

/home/vanessa/Desktop/hello-kitty.txt # copied to root of container

/home/vanessa/Desktop/party_dinosaur.gif /opt/the-party-dino.gif #

%environment

VARIABLE=MEATBALLVALUE

export VARIABLE

%labels

AUTHOR vsochat@stanford.edu

%post

apt-get update && apt-get -y install python3 git wget

mkdir /data

echo "The post section is where you can install, and configure your container."

To build a container from this definition file (assuming it is a file named Singularity), you would call build like so:

$ sudo singularity build ubuntu.simg Singularity

Introduction¶

This document will introduce you to Singularity, and the links in the bar to the left will give you more detail on using the software. If you want to get a quick rundown, see our quickstart. If you want to understand which commands are best fit for your usecase, see our build flow page. There is also a separate Singularity Administration Guide that targets system administrators, so if you are a service provider, or an interested user, it is encouraged that you read that document as well.

Welcome to Singularity!¶

A High Level View of Singularity¶

%SERVER and %CLUSTER are large expensive systems with resources far exceeding those of my personal workstation. But because the are shared systems, no users have root access. The environments are tightly controlled and managed by a staff of system administrators. To keep these systems secure, only the system administrators are granted root access and they control the state of the operating systems and installed applications. If a user is able to escalate to root (even within a container) on %SERVER or %CLUSTER, they can do bad things to the network, cause denial of service to the host (as well as other hosts on the same network), and may have unrestricted access to file systems reachable by the container.

- Copying or branching an entire container is as simple as

- Permission/access to the container is managed via standard file system permissions

- Large scale performance (especially over parallel file systems) is very efficient

- No caching of the image contents to run (especially nice on clusters)

- Containers are compressed and consume very little disk space

- Images can serve as stand-alone programs, and can be executed like any other program on the host

Copying, sharing, branching, and distributing your image¶

Supported container formats¶

- squashfs: the default container format is a compressed read-only file system that is widely used for things like live CDs/USBs and cell phone OS’s

- ext3: (also called ) a writable image file containing an ext3 file system that was the default container format prior to Singularity version 2.4

- directory: (also called ) standard Unix directory containing a root container image

- tar.gz: zlib compressed tar archive

- tar.bz2: bzip2 compressed tar archive

- tar: uncompressed tar archive

Supported URIs¶

Singularity also supports several different mechanisms for obtaining the images using a standard URI format.

- shub:// Singularity Hub is our own registry for Singularity containers. If you want to publish a container, or give easy access to others from their command line, or enable automatic builds, you should build it on `Singularity Hub`_.

- docker:// Singularity can pull Docker images from a Docker registry, and will run them non-persistently (e.g. changes are not persisted as they can not be saved upstream). Note that pulling a Docker image implies assembling layers at runtime, and two subsequent pulls are not guaranteed to produce an identical image.

- instance:// A Singularity container running as service, called an instance, can be referenced with this URI.

$ singularity exec dummy.img xterm # run xterm from within the container

$ singularity exec dummy.img python script.py # run a script on the host system using container's python

$ singularity exec dummy.img python < /path/to/python/script.py # do the same via redirection

$ cat /path/to/python/script.py | singularity exec dummy.img python # do the same via a pipe

You can even run MPI executables within the container as simply as:

$ mpirun -np X singularity exec /path/to/container.img /usr/bin/mpi_program_inside_container (mpi program args)

When executing container commands, the Singularity process flow can be generalized as follows:

- Singularity application is invoked

- Global options are parsed and activated

- The Singularity command (subcommand) process is activated

- Subcommand options are parsed

- The appropriate sanity checks are made

- Environment variables are set

- The Singularity Execution binary is called ()

- Sexec determines if it is running privileged and calls the code if necessary

- Namespaces are created depending on configuration and process requirements

- The Singularity image is checked, parsed, and mounted in the namespace

- Bind mount points are setup so that files on the host are visible in the container

- The namespace is used to virtualize a new root file system

- Singularity calls and Singularity process itself is replaced by the process inside the container

- When the process inside the container exits, all namespaces collapse with that process, leaving a clean system

All of the above steps take approximately 15-25 thousandths of a second to run, which is fast enough to seem instantaneous.

The Singularity Usage Workflow¶

Singularity workflow

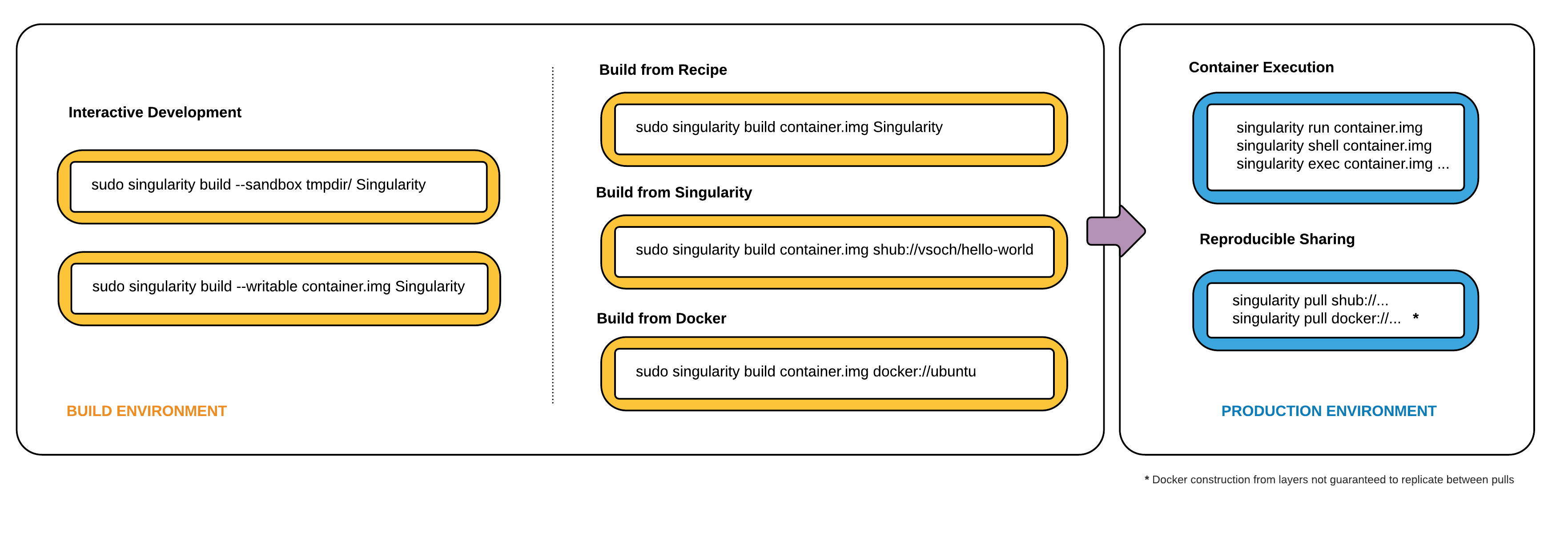

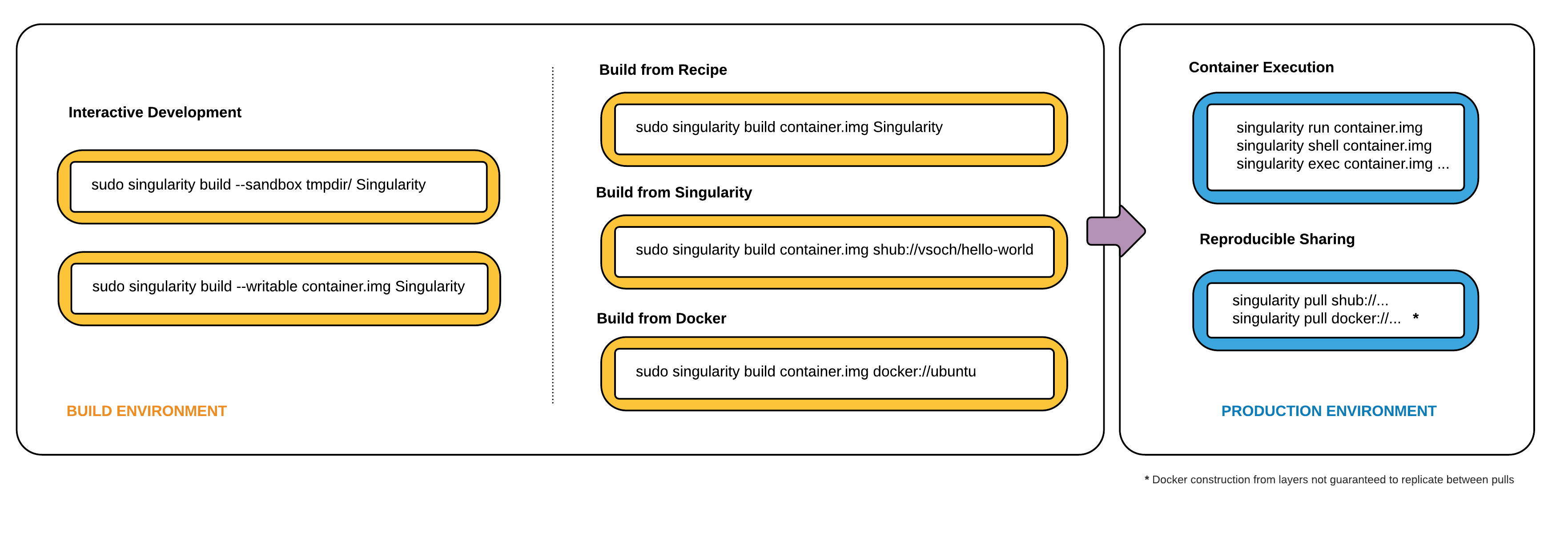

- develop and test containers using (build into a writable directory) or (build into a writable ext3 image)

- build your production containers with a squashfs filesystem.

- <a href=”#sec:build”>build</a>: Build a container on your user endpoint or build environment

- <a href=”#sec:exec”>exec</a>: Execute a command to your container

- <a href=”#sec:inspect”>inspect</a>: See labels, run and test scripts, and environment variables

- <a href=”#sec:pull”>pull</a>: pull an image from Docker or Singularity Hub

- <a href=”#sec:run”>run</a>: Run your image as an executable

- <a href=”#sec:shell”>shell</a>: Shell into your image

Image Commands

- <a href=”#sec:imageimport”>image.import</a>: import layers or other file content to your image

- <a href=”#sec:imageexport”>image.export</a>: export the contents of the image to tar or stream

- <a href=”#sec:imagecreate”>image.create</a>: create a new image, using the old ext3 filesystem

- <a href=”#sec:imageexpand”>image.expand</a>: increase the size of your image (old ext3)

- <a href=”#sec:instances”>instances</a>: Start, stop, and list container instances

Deprecated Commands The following commands are deprecated in 2.4 and will be removed in future releases.

- <a href=”#sec:bootstrap”>bootstrap</a>: Bootstrap a container recipe

Support¶

Have a question, or need further information? Reach out to us.

Installation¶

This document will guide you through the process of installing Singularity from source with the version and location of your choice.

Before you begin¶

$ sudo apt-get update && \

sudo apt-get install \

python \

dh-autoreconf \

build-essential \

libarchive-dev

$ sudo yum update && \

sudo yum groupinstall 'Development Tools' && \

sudo yum install libarchive-devel

Install the master branch¶

The following commands will install the latest version of the GitHub repo master branch to .

$ git clone https://github.com/singularityware/singularity.git

$ cd singularity

$ ./autogen.sh

$ ./configure --prefix=/usr/local --sysconfdir=/etc

$ make

$ sudo make install

Install a specific release¶

$ VER=2.5.1

$ wget https://github.com/singularityware/singularity/releases/download/$VER/singularity-$VER.tar.gz

$ tar xvf singularity-$VER.tar.gz

$ cd singularity-$VER

$ ./configure --prefix=/usr/local --sysconfdir=/etc

$ make

$ sudo make install

Install the development branch¶

$ git clone https://github.com/singularityware/singularity.git

$ cd singularity

$ git fetch

$ git checkout development

$ ./autogen.sh

$ ./configure --prefix=/usr/local --sysconfdir=/etc

$ make

$ sudo make install

Remove an old version¶

Let’s say that we installed Singularity to . To remove it completely, you need to hit all of the following:

$ sudo rm -rf /usr/local/libexec/singularity

$ sudo rm -rf /usr/local/etc/singularity

$ sudo rm -rf /usr/local/include/singularity

$ sudo rm -rf /usr/local/lib/singularity

$ sudo rm -rf /usr/local/var/lib/singularity/

$ sudo rm /usr/local/bin/singularity

$ sudo rm /usr/local/bin/run-singularity

$ sudo rm /usr/local/etc/bash_completion.d/singularity

$ sudo rm /usr/local/man/man1/singularity.1

$ sudo rm -rf /some/temp/dir

What should you do next? You can check out the a href=“sec:quickstart”>quickstart</a> guide, or learn how to interact with your container via the a href=”sec:shell”>shell</a>, a href=“sec:exec”>exec</a> , or a href=”sec:run”>run</a> commands. Or click next below to continue reading.

Build a Container¶

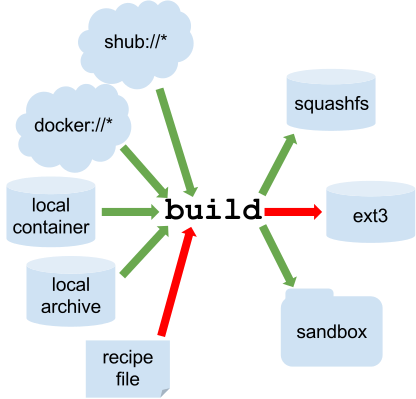

is the “Swiss army knife” of container creation. You can use it to download and assemble existing containers from external resources like `Singularity Hub`_ and Docker Hub. You can use it to convert containers between the various formats supported by Singularity. And you can use it in conjunction with a <a href=”#sec:recipefile”>Singularity recipe</a> file to create a container from scratch and customized it to fit your needs.

Overview¶

- URI beginning with shub:// to build from Singularity Hub

- URI beginning with docker:// to build from Docker Hub

- path to a existing container on your local machine

- path to a directory to build from a sandbox

- path to an archive in .tar or compressed .tar.gz format

- path to a <a href=”#sec:recipefile”>Singularity recipe file</a>

- compressed read-only squashfs file system suitable for production (default)

- writable ext3 file system suitable for interactive development ( option )

- writable (ch)root directory called a sandbox for interactive development ( option)

Singularity build process

Downloading a existing container from Singularity Hub¶

You can use the build command to download a container from Singularity Hub.

$ singularity build lolcow.simg shub://GodloveD/lolcow

Downloading a existing container from Docker Hub¶

You can use to download layers from Docker Hub and assemble them into Singularity containers.

$ singularity build lolcow.simg docker://godlovedc/lolcow

Creating - -writable images and - -sandbow directories¶

$ sudo singularity build --writable lolcow.img shub://GodloveD/lolcow

$ sudo singularity shell --writable lolcow.img

If you wanted to create a container within a writable directory (called a sandbox) you could do so with the option. It’s possible to create a sandbox without root privileges, but to ensure proper file permissions it is recommended to do so as root.

$ sudo singularity build --sandbox lolcow/ shub://GodloveD/lolcow

$ sudo singularity shell --writable lolcow/

Converting containers from one format to another¶

If you already have a container saved locally, you can use it as a target to build a new container. This allows you convert containers from one format to another. For example if you had a squashfs container called and wanted to convert it to a writable ext3 container called you could:

$ sudo singularity build --writable development.img production.simg

$ singularity build --sandbox development/ production.simg

If you omit any options you can also convert your sandbox back to a read-only compressed squashfs image suitable for use in a production environment:

$ singularity build production2 development/

Building containers from Singularity recipe files¶

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu:16.04

%post

apt-get -y update

apt-get -y install fortune cowsay lolcat

%environment

export LC_ALL=C

export PATH=/usr/games:$PATH

%runscript

fortune | cowsay | lolcat

You can do so with the following command.

$ sudo singularity build lolcow.simg Singularity

The command requires just as installing software on your local machine requires root privileges.

If you only want to build a single section of your Singularity recipe file use the option. For instance, if you have edited the section of a long Singularity recipe and don’t want to completely re-build the container, you could re-build only the section like so:

$ sudo singularity build --section environment image.simg Singularity

Under normal build conditions, the Singularity recipe file is saved into a container’s meta-data so that there is a record showing how the container was built. Using the option may render this meta-data useless, so use care if you value reproducibility.

If you don’t want to run the section during the container build, you can skip it with the option. For instance, maybe you are building a container intended to run in a production environment with GPUs. But perhaps your local build resource does not have GPUs. You want to include a section that runs a short validation but you don’t want your build to exit with an error because it cannot find a GPU on your system.

$ sudo singularity build GPU.simg --notest Singularity

CHECKS OPTIONS:

-c|--checks enable checks

-t|--tag specify a check tag (not default)

-l|--low Specify low threshold (all checks, default)

-m|--med Perform medium and high checks

-h|--high Perform only checks at level high

When you add the option along with applicable tags to the command Singularity will run the desired checks on your container at build time. See for available tags.

More Build topics¶

- If you want to customize the cache location (where Docker layers are downloaded on your system), specify Docker credentials, or any custom tweaks to your build environment, see a href=”#sec:buildenv”>build environment</a>.

- If you want to make internally modular containers, check out the getting started guide here

- If you want to build your containers on Singularity Hub, (because you don’t have root access on a Linux machine or want to host your container on the cloud) check out this guide

Build Environment¶

It’s commonly the case that you want to customize your build environment, such as specifying a custom cache directory for layers, or sending your Docker Credentials to the registry endpoint. Here we will discuss those things

Cache Folders¶

To make download of layers for build and <a href=”#sec:pull”>pull</a> faster and less redundant, we use a caching strategy. By default, the Singularity software will create a set of folders in your directory for docker layers, Singularity Hub images, and Docker metadata, respectively:

$HOME/.singularity

$HOME/.singularity/docker

$HOME/.singularity/shub

$HOME/.singularity/metadata

Fear not, you have control to customize this behavior! If you don’t want the cache to be created (and a temporary directory will be used), set to True/yes, or if you want to move it elsewhere, set to the full path where you want to cache. Remember that when you run commands as sudo this will use root’s home at and not your user’s home.

Temporary Folders¶

singularity exec docker://busybox /bin/sh

SINGULARITY_LOCALCACHEDIR=/tmp/pancakes

export SINGULARITY_LOCALCACHEDIR

singularity exec docker://busybox /bin/sh

Pull Folder¶

For details about customizing the output location of a href=“sec:pull”>pull</a>, see the a href=”sec:pull”>pull docs</a>. You have the similar ability to set it to be something different, or to customize the name of the pulled image.

Environment Variables¶

- First preference goes to environment variable set at runtime

- Second preference goes to default defined in this file

- Then, if neither is found, null is returned except in the case that . A variable not found will system exit with an error.

- Variables that should not be displayed in debug logger are set with , and are only reported to be defined.

For boolean variables, the following are acceptable for True, with any kind of capitalization or not:

("yes", "true", "t", "1","y")

Cache¶

singularity --debug run docker://busybox echo "pizza!"

...

DEBUG [U=1000,P=960] s_rmdir() Removing directory: /tmp/.singularity-runtime.oArO0k

The following variables have defaults that can be customized by you via environment variables at runtime.

Docker¶

Singularity Hub¶

/usr/bin/python

and we would parse it into the runscript as:

exec /usr/bin/python "$@"

However, it might be the case that the user does not want this. For this reason, we have the environmental variable . If defined as yes/y/1/True/true, etc., then the runscript will remain as .

Container Recipes¶

A Singularity Recipe is the driver of a custom build, and the starting point for designing any custom container. It includes specifics about installation software, environment variables, files to add, and container metadata. You can even write a help section, or define modular components in the container called based on the Scientific Filesystem.

Overview¶

A Singularity Recipe file is divided into several parts:

- Header: The Header describes the core operating system to build within the container. Here you will configure the base operating system features that you need within your container. Examples of this include, what distribution of Linux, what version, what packages must be part of a core install.

- Sections: The rest of the definition is comprised of sections, sometimes called scriptlets or blobs of data. Each section is defined by a character followed by the name of the particular section. All sections are optional. Sections that are executed at build time are executed with the interpreter and can accept options. Similarly, sections that produce scripts to be executed at runtime can accept options intended for

The header is at the top of the file, and tells Singularity the base Operating System that it should use to build the container. It is composed of several keywords. Specifically:

- : references the kind of base you want to use (e.g., docker, debootstrap, shub). For example, a shub bootstrap will pull containers for shub as bases. A Docker bootstrap will pull docker layers to start your image. For a full list see a href=”#sec:buildcontainer”>build</a>

- : is the named container (shub) or reference to layers (Docker) that you want to use (e.g., vsoch/hello-world)

Bootstrap: shub

From: vsoch/hello-world

A build that uses a mirror to install Centos-7 might look like this:

Bootstrap: yum

OSVersion: 7

MirrorURL: http://mirror.centos.org/centos-%{OSVERSION}/%{OSVERSION}/os/$basearch/

Include: yum

- shub (images hosted on Singularity Hub)

- `docker`_ (images hosted on Docker Hub)

- localimage (images saved on your machine)

- yum (yum based systems such as CentOS and Scientific Linux)

- debootstrap (apt based systems such as Debian and Ubuntu)

- arch (Arch Linux)

- busybox (BusyBox)

- zypper (zypper based systems such as Suse and OpenSuse)

$ sudo singularity build roar.simg Singularity

%help¶

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu

%help

Help me. I'm in the container.

And it will work when the user asks the container for help.

$ singularity help roar.simg

Help me. I'm in the container.

%setup¶

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu

%help

Help me. I'm in the container.

%setup

touch ${SINGULARITY_ROOTFS}/tacos.txt

touch avocados.txt

Importantly, notice that the avocados file isn’t relative to $SINGULARITY_ROOTFS, so we would expect it not to be in the image. Is tacos there?

$ singularity exec roar.simg ls /

bin environment lib mnt root scif sys usr

boot etc lib64 opt run singularity **tacos.txt** var

dev home media proc sbin srv tmp

Yes! And avocados.txt isn’t inside the image, but in our present working directory:

$ ls

avocados.txt roar.simg Singularity

%files¶

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu

%help

Help me. I'm in the container.

# Both of the below are copied before %post

# 1. This is how to copy files for legacy < 2.3

%setup

touch ${SINGULARITY_ROOTFS}/tacos.txt

touch avocados.txt

# 2. This is how to copy files for >= 2.3

%files

avocados.txt

avocados.txt /opt

Notice that I’m adding the same file to two different places. For the first, I’m adding the single file to the root of the image. For the second, I’m adding it to opt. Does it work?

$ singularity exec roar.simg ls /

singularity exec roar.simg ls /

**avocados.txt** dev home media proc sbin srv tmp

bin environment lib mnt root scif sys usr

boot etc lib64 opt run singularity **tacos.txt** var

$ singularity exec roar.simg ls /opt

**avocados.txt**

We have avocados!

%labels¶

To store metadata with your container, you can add them to the section. They will be stored in the file as metadata within your container. The general format is a followed by a . Labels from Docker bootstraps will be carried forward here. Let’s add to our example:

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu

%help

Help me. I'm in the container.

%setup

touch ${SINGULARITY_ROOTFS}/tacos.txt

touch avocados.txt

%files

avocados.txt

avocados.txt /opt

%labels

Maintainer Vanessasaurus

Version v1.0

The easiest way to see labels is to inspect the image:

$ singularity inspect roar.simg

{

"org.label-schema.usage.singularity.deffile.bootstrap": "docker",

"MAINTAINER": "Vanessasaurus",

"org.label-schema.usage.singularity.deffile": "Singularity",

"org.label-schema.usage": "/.singularity.d/runscript.help",

"org.label-schema.schema-version": "1.0",

"VERSION": "v1.0",

"org.label-schema.usage.singularity.deffile.from": "ubuntu",

"org.label-schema.build-date": "2017-10-02T17:00:23-07:00",

"org.label-schema.usage.singularity.runscript.help": "/.singularity.d/runscript.help",

"org.label-schema.usage.singularity.version": "2.3.9-development.g3dafa39",

"org.label-schema.build-size": "1760MB"

}

You’ll notice some other labels that are captured automatically from the build process. You can read more about labels and metadata a href=”#sec:envandmetadata”>here</a> .

%environment¶

- during build: the section is written to a file in the container’s metadata folder. This file is not sourced.

- during runtime: the file written to the container’s metadata folder is sourced.

Since the file is ultimately sourced, you should generally use the same conventions that you might use in a bashrc or profile. In the example below, the variables and would not be available during build, but when the container is finished and run:

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu

%help

Help me. I'm in the container.

%setup

touch ${SINGULARITY_ROOTFS}/tacos.txt

touch avocados.txt

%files

avocados.txt

avocados.txt /opt

%labels

Maintainer Vanessasaurus

Version v1.0

%environment

VADER=badguy

LUKE=goodguy

SOLO=someguy

export VADER LUKE SOLO

For the rationale behind this approach and why we do not source the %environment section at build time, refer to this issue. When the container is finished, you can easily see environment variables also with inspect, and this is done by showing the file produced above:

$ singularity inspect -e roar.simg # Custom environment shell code should follow

VADER=badguy

LUKE=goodguy

SOLO=someguy

export VADER LUKE SOLO

or in the case of variables generated at build time, you can add environment variables to your container in the section (see below) using the following syntax:

%post

echo 'export JAWA_SEZ=wutini' >> $SINGULARITY_ENVIRONMENT

When we rebuild, is it added to the environment?

singularity exec roar.simg env | grep JAWA

JAWA_SEZ=wutini

%post¶

Commands in the section are executed within the container after the base OS has been installed at build time. This is where the meat of your setup will live, including making directories, and installing software and libraries. We will jump from our simple use case to show a more realistic scientific container. Here we are installing yum, openMPI, and other dependencies for a Centos7 bootstrap:

%post

echo "Installing Development Tools YUM group"

yum -y groupinstall "Development Tools"

echo "Installing OpenMPI into container..."

# Here we are at the base, /, of the container

git clone https://github.com/open-mpi/ompi.git

# Now at /ompi

cd ompi

./autogen.pl

./configure --prefix=/usr/local

make

make install

/usr/local/bin/mpicc examples/ring_c.c -o /usr/bin/mpi_ring

You cannot copy files from the host to your container in this section, but you can of course download with commands like and and .

%runscript¶

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu

%help

Help me. I'm in the container.

%setup

touch ${SINGULARITY_ROOTFS}/tacos.txt

touch avocados.txt

%files

avocados.txt

avocados.txt /opt

%labels

Maintainer Vanessasaurus

Version v1.0

%environment

VADER=badguy

LUKE=goodguy

SOLO=someguy

export VADER LUKE SOLO

%post

echo 'export JAWA_SEZ=wutini' >> $SINGULARITY_ENVIRONMENT

%runscript

echo "Rooooar!"

echo "Arguments received: $*"

exec echo "$@"

In this particular runscript, the arguments are printed as a single string () and then they are passed to echo via a quoted array () which ensures that all of the arguments are properly parsed by the executed command. Using the command is like handing off the calling process to the one in the container. The final command (the echo) replaces the current entry in the process table (which originally was the call to Singularity). This makes it so the runscript shell process ceases to exist, and the only process running inside this container is the called echo command. This could easily be another program like python, or an analysis script. Running it, it works as expected:

$ singularity run roar.simg

Rooooar!

Arguments received:

$ singularity run roar.simg one two

Rooooar!

Arguments received: one two

one two

%test¶

You may choose to add a section to your definition file. This section will be run at the very end of the build process and will give you a chance to validate the container during the bootstrap process. You can also execute this scriptlet through the container itself, such that you can always test the validity of the container itself as you transport it to different hosts. Extending on the above Open MPI , consider this real world example:

%test

/usr/local/bin/mpirun --allow-run-as-root /usr/bin/mpi_test

$ sudo singularity build --notest mpirun.simg Singularity

This argument is useful in cases where you need hardware that is available during runtime, but is not available on the host that is building the image.

Apps¶

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu

%environment

VADER=badguy

LUKE=goodguy

SOLO=someguy

export VADER LUKE SOLO

%labels

Maintainer Vanessasaur

##############################

# foo

##############################

%apprun foo

exec echo "RUNNING FOO"

%applabels foo

BESTAPP=FOO

export BESTAPP

%appinstall foo

touch foo.exec

%appenv foo

SOFTWARE=foo

export SOFTWARE

%apphelp foo

This is the help for foo.

%appfiles foo

avocados.txt

##############################

# bar

##############################

%apphelp bar

This is the help for bar.

%applabels bar

BESTAPP=BAR

export BESTAPP

%appinstall bar

touch bar.exec

%appenv bar

SOFTWARE=bar

export SOFTWARE

$ singularity apps roar.simg

bar

foo

Help me with bar!

$ singularity help --app bar roar.simg

This is the help for bar.

Run foo

singularity run --app foo roar.simg

RUNNING FOO

$ singularity exec --app foo roar.simg env | grep SOFTWARE

SOFTWARE=foo

$ singularity exec --app bar roar.simg env | grep SOFTWARE

SOFTWARE=bar

Examples¶

Best Practices for Build Recipes¶

When crafting your recipe, it is best to consider the following:

- To make your container internally modular, use a href=”#sec:scifapps”>SCI-F apps</a>. Shared dependencies (between app modules) can go under .

- For global installs to , install packages, programs, data, and files into operating system locations (e.g. not , , or any other directories that might get commonly binded on).

- Make your container speak for itself. If your runscript doesn’t spit out help, write a or or section. A good container tells the user how to interact with it.

- If you require any special environment variables to be defined, add them the and sections of the build recipe.

- Files should never be owned by actual users, they should always be owned by a system account (UID less than 500).

- Ensure that the container’s , , , and no other sensitive files have anything but the bare essentials within them.

- It is encouraged to build containers from a recipe instead of a sandbox that has been manually changed. This ensures greatest possibility of reproducibility and mitigates the black box effect.

Are you a recipe pro and now ready to build? Take a look at the a href=”#sec:buildcontainer”>build</a> documentation.

Singularity Flow¶

Building Images¶

The diagram below is a visual depiction of how you can use Singularity to build images. The high level idea is that we have two environments:

- a build environment (where you have sudo privileges) to test and build your container

- a production environment where you run your container

Singularity production images are immutable. This is a feature added as of Singularity 2.4, and it ensures a higher level of reproducibility and verification of images. To read more about the details, check out the a href=”#sec:buildcontainer”>build</a> docs. However, immutability is not so great when you are testing, debugging, or otherwise want to quickly change your image. We will proceed by describing a typical workflow of developing first, building a final image, and using it in production.

If you want a writable image or folder for developing, you have two options:

- build into a directory that has writable permissions using the option

- build into an ext3 image file, that has writable permissions with the option

In both cases you will need to execute your container with the option at runtime for your changes to be persistent.

Sandbox Folder¶

$ sudo singularity build --sandbox ubuntu/ docker://ubuntu

Docker image path: index.docker.io/library/ubuntu:latest

Cache folder set to /root/.singularity/docker

Importing: base Singularity environment

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:9fb6c798fa41e509b58bccc5c29654c3ff4648b608f5daa67c1aab6a7d02c118.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:3b61febd4aefe982e0cb9c696d415137384d1a01052b50a85aae46439e15e49a.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:9d99b9777eb02b8943c0e72d7a7baec5c782f8fd976825c9d3fb48b3101aacc2.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:d010c8cf75d7eb5d2504d5ffa0d19696e8d745a457dd8d28ec6dd41d3763617e.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:7fac07fb303e0589b9c23e6f49d5dc1ff9d6f3c8c88cabe768b430bdb47f03a9.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/metadata/sha256:22e289880847a9a2f32c62c237d2f7e3f4eae7259bf1d5c7ec7ffa19c1a483c8.tar.gz

Building image from sandbox: ubuntu/

Singularity container built: ubuntu/

$ tree -L 1 ubuntu

ubuntu

├── bin

├── boot

├── dev

├── environment -> .singularity.d/env/90-environment.sh

├── etc

├── home

├── lib

├── lib64

├── media

├── mnt

├── opt

├── proc

├── root

├── run

├── sbin

├── singularity -> .singularity.d/runscript

├── srv

├── sys

├── tmp

├── usr

└── var

And you can shell into it just like a normal container.

$ singularity shell ubuntu

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

Singularity ubuntu:~/Desktop> touch /hello.txt

touch: cannot touch '/hello.txt': Permission denied

$ sudo singularity shell ubuntu

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

Singularity ubuntu:/home/vanessa/Desktop> touch /hello.txt

Writable Image¶

If you prefer to work with a writable image file rather than a directory, you can perform a similar development build and specify the option. This will produce an image that is writable with an ext3 file system. Unlike the sandbox, it is a single image file.

$ sudo singularity build --writable ubuntu.img docker://ubuntu

Docker image path: index.docker.io/library/ubuntu:latest

Cache folder set to /root/.singularity/docker

Importing: base Singularity environment

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:9fb6c798fa41e509b58bccc5c29654c3ff4648b608f5daa67c1aab6a7d02c118.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:3b61febd4aefe982e0cb9c696d415137384d1a01052b50a85aae46439e15e49a.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:9d99b9777eb02b8943c0e72d7a7baec5c782f8fd976825c9d3fb48b3101aacc2.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:d010c8cf75d7eb5d2504d5ffa0d19696e8d745a457dd8d28ec6dd41d3763617e.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:7fac07fb303e0589b9c23e6f49d5dc1ff9d6f3c8c88cabe768b430bdb47f03a9.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/metadata/sha256:22e289880847a9a2f32c62c237d2f7e3f4eae7259bf1d5c7ec7ffa19c1a483c8.tar.gz

Building image from sandbox: /tmp/.singularity-build.VCHPpP

Creating empty Singularity writable container 130MB

Creating empty 162MiB image file: ubuntu.img

Formatting image with ext3 file system

Image is done: ubuntu.img

Building Singularity image...

Cleaning up...

Singularity container built: ubuntu.img

You can use this image with commands like , , , and if you want to change the image you must use the flag. As before, it’s a good idea to issue these commands as root to ensure you have the proper permissions to write.

$ sudo singularity shell --writable ubuntu.img

Development Tip! When building containers, it often is the case that

you will have a lot of testing of installation commands, and if

building a production image, one error will stop the entire build.

If you interactively write the build recipe with one of these

writable containers, you can debug as you go, and then build the

production (squashfs) container without worrying that it will error

and need to be started again.

Let’s set the scene - we just finished building our perfect hello world container. It does a fantastic hello-world analysis, and we have written a paper on it! We now want to build an immutable container - meaning that if someone obtained our container and tried to change it, they could not. They could easily use the same recipe that you used (it is provided as metadata inside the container), or convert your container to one of the writable formats above using . So your work can still be extended.

Recommended Production Build¶

What we want for production is a build into a squashfs image . Squashfs is a read only, and compressed filesystem, and well suited for confident archive and re-use of your hello-world. To build a production image, just remove the extra options:

sudo singularity build ubuntu.simg docker://ubuntu

Docker image path: index.docker.io/library/ubuntu:latest

Cache folder set to /root/.singularity/docker

Importing: base Singularity environment

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:9fb6c798fa41e509b58bccc5c29654c3ff4648b608f5daa67c1aab6a7d02c118.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:3b61febd4aefe982e0cb9c696d415137384d1a01052b50a85aae46439e15e49a.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:9d99b9777eb02b8943c0e72d7a7baec5c782f8fd976825c9d3fb48b3101aacc2.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:d010c8cf75d7eb5d2504d5ffa0d19696e8d745a457dd8d28ec6dd41d3763617e.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:7fac07fb303e0589b9c23e6f49d5dc1ff9d6f3c8c88cabe768b430bdb47f03a9.tar.gz

Importing: /root/.singularity/metadata/sha256:22e289880847a9a2f32c62c237d2f7e3f4eae7259bf1d5c7ec7ffa19c1a483c8.tar.gz

Building Singularity image...

Cleaning up...

Singularity container built: ubuntu.simg

Production Build from Sandbox¶

We understand that it might be wanted to build a Singularity (squashfs) from a previous development image. While we advocate for the first approach, we support this use case. To do this, given our folder called “ubuntu/” we made above:

sudo singularity build ubuntu.simg ubuntu/

Bind Paths and Mounts¶

If enabled by the system administrator, Singularity allows you to map directories on your host system to directories within your container using bind mounts. This allows you to read and write data on the host system with ease.

Overview¶

When Singularity ‘swaps’ the host operating system for the one inside your container, the host file systems becomes inaccessible. But you may want to read and write files on the host system from within the container. To enable this functionality, Singularity will bind directories back in via two primary methods: system-defined bind points and conditional user-defined bind points.

The system administrator has the ability to define what bind points will be included automatically inside each container. The bind paths are locations on the host’s root file system which should also be visible within the container. Some of the bind paths are automatically derived (e.g. a user’s home directory) and some are statically defined (e.g. bind path in the Singularity configuration file). In the default configuration, the directories , , , , and are among the system-defined bind points.

Specifying Bind Paths¶

$ singularity shell -B /tmp:/scratch /tmp/Centos7-ompi.img

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

Singularity.Centos7-ompi.img> ls /scratch

ssh-7vywtVeOez systemd-private-cd84c81dda754fe4a7a593647d5a5765-ntpd.service-12nMO4

$ singularity shell -B /opt,/data:/mnt /tmp/Centos7-ompi.img

This will bind on the host to in the container and on the host to in the container. Using the environment variable instead of the command line argument, this would be:

$ export SINGULARITY_BINDPATH="/opt,/data:/mnt"

$ singularity shell /tmp/Centos7-ompi.img

Using the environment variable , you can bind directories even when you are running your container as an executable file with a runscript. If you bind many directories into your Singularity containers and they don’t change, you could even benefit by setting this variable in your file.

Binding with Overlay¶

If a bind path is requested and the bind point does not exist within the container, a warning message will be displayed and Singularity will continue trying to start the container. For example:

$ singularity shell --bind /global /tmp/Centos7-ompi.img

WARNING: Non existent bind point (directory) in container: '/global'

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

Singularity.Centos7-ompi.img>

Even though did not exist inside the container, the shell command printed a warning but continued on. If overlay is available and enabled, you will find that we no longer get the error and is created and accessible as expected:

$ singularity shell --bind /global /tmp/Centos7-ompi.img

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

Singularity.Centos7-ompi.img>

In this case, Singularity dynamically created the necessary bind point in your container. Without overlay, you would have needed to manually create the directory inside your container.

Persistent Overlays¶

Persistent overlay images are new to version 2.4! This feature allows you to overlay a writable file system on an immutable read-only container for the illusion of read-write access.

Overview¶

Usage¶

To use a persistent overlay, you must first have a container.

$ singularity build ubuntu.simg shub://GodloveD/ubuntu

Then you must create a writable, ext3 image. We can do so with the command:

$ singularity image.create my-overlay.img

Now you can use this overlay image with your container. Note that it is not necessary to be root to use an overlay partition, but this will ensure that we have write privileges where we want them.

$ sudo singularity shell --overlay my-overlay.img ubuntu.simg

Singularity ubuntu.simg:~> touch /foo

Singularity ubuntu.simg:~> apt-get install -y vim

Singularity ubuntu.simg:~> which vim

/usr/bin/vim

Singularity ubuntu.simg:~> exit

$ sudo singularity shell --overlay my-overlay.img ubuntu.simg

Singularity ubuntu.simg:~> ls /foo

/foo

Singularity ubuntu.simg:~> which vim

/usr/bin/vim

Singularity ubuntu.simg:~> exit

If you mount your container without the option, your changes will be gone.

$ sudo singularity shell ubuntu.simg

Singularity ubuntu.simg:~> ls /foo

ls: cannot access 'foo': No such file or directory

Singularity ubuntu.simg:~> which vim

Singularity ubuntu.simg:~> exit

Running Services¶

Singularity 2.4 introduces the ability to run “container instances”, allowing you to run services (e.g. Nginx, MySQL, etc…) using Singularity. A container instance, simply put, is a persistent and isolated version of the container image that runs in the background.

Why container instances?¶

that is pretty simple, I install nginx and start the service:

apt-get update && apt-get install -y nginx

service nginx start

Container Instances in Singularity¶

With Singularity 2.4 and the addition of container instances, the ability to cleanly, reliably, and safely run services in a container is here. First, let’s put some commands that we want our instance to execute into a script. Let’s call it a . This fits into a definition file like so:

%startscript

service nginx start

Now let’s say we build a container with that startscript into an image called and we want to run an nginx service. All we need to do is start the instance with the command, and the startscript will run inside the container automatically:

[command] [image] [name of instance]

$ singularity instance.start nginx.img web

When we run that command, Singularity creates an isolated environment for the container instances’ processes/services to live inside. We can confirm that this command started an instance by running the instance.list command like so:

$ singularity instance.list

INSTANCE NAME PID CONTAINER IMAGE

web 790 /home/mibauer/nginx.img

If we want to run multiple instances from the same image, it’s as simple as running the command multiple times. The instance names are an identifier used to uniquely describe an instance, so they cannot be repeated.

$ singularity instance.start nginx.img web1

$ singularity instance.start nginx.img web2

$ singularity instance.start nginx.img web3

And again to confirm that the instances are running as we expected:

$ singularity instance.list

INSTANCE NAME PID CONTAINER IMAGE

web1 790 /home/mibauer/nginx.img

web2 791 /home/mibauer/nginx.img

web3 792 /home/mibauer/nginx.img

If the service you want to run in your instance requires a bind mount, then you must pass the option when calling . For example, if you wish to capture the output of the container instance which is placed at inside the container you could do:

$ singularity instance.start -B output/dir/outside/:/output/ nginx.img web1

If you want to poke around inside of your instance, you can do a normal command, but give it the instance URI:

$ singularity shell instance://web1

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

Singularity pdf_server.img:~/>

Similarly, you can use the commands on instances:

$ singularity run instance://web1

$ singularity exec instance://web1 ps -ef

When using with an instance URI, the will be executed inside of the instance. Similarly with , it will execute the given command in the instance.

When you are finished with your instance you can clean it up with the command like so:

$ singularity instance.stop web1

$ singularity instance.stop \*

$ singularity instance.stop -a

Note that you must escape the wildcard with a backslash like this to pass it properly.

Nginx “Hello-world” in Singularity¶

Let’s take a look at setting up a sample nginx web server using instances in Singularity. First we will just create a basic definition file:

Bootstrap: docker

From: nginx

Includecmd: no

%startscript

nginx

All this does is download the official nginx Docker container, convert it to a Singularity image, and tell it to run nginx when you start the instance. Since we’re running a web server, we’re going to run the following commands as root.

# singularity build nginx.img Singularity

# singularity instance.start nginx.img web1

Just like that we’ve downloaded, built, and ran an nginx Singularity image. And to confirm that it’s correctly running:

$ curl localhost

127.0.0.1 - - [06/Oct/2017:21:46:43 +0000] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 612 "-" "curl/7.47.0" "-"

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Welcome to nginx!</title>

<style>

body {

width: 35em;

margin: 0 auto;

font-family: Tahoma, Verdana, Arial, sans-serif;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Welcome to nginx!</h1>

<p>If you see this page, the nginx web server is successfully installed and

working. Further configuration is required.</p>

<p>For online documentation and support please refer to

<<a href="#http://nginx.org/">nginx.org</a>.<br/>

Commercial support is available at

<<a href="#http://nginx.com/">nginx.com</a>.</p>

<p><em>Thank you for using nginx.</em></p>

</body>

</html>

Putting all together¶

In this section, we will demonstrate an example of packaging a service into a container and running it. The service we will be packaging is an API server that converts a web page into a PDF, and can be found here. The final example can be found here on GitHub, and here on SingularityHub. If you wish to just download the final image directly from Singularity Hub, simply run .

Building the image¶

To begin, we need to build the image. When looking at the GitHub page of the , we can see that it is a Node 8 server that uses headless Chromium called Puppeteer. Let’s first choose a base from which to build our container, in this case I used the docker image which comes pre-installed with Node 8:

Bootstrap: docker

From: node:8

Includecmd: no

%post

apt-get update

apt-get install -yq gconf-service libasound2 libatk1.0-0 libc6 libcairo2 libcups2 \

libdbus-1-3 libexpat1 libfontconfig1 libgcc1 libgconf-2-4 libgdk-pixbuf2.0-0 \

libglib2.0-0 libgtk-3-0 libnspr4 libpango-1.0-0 libpangocairo-1.0-0 libstdc++6 \

libx11-6 libx11-xcb1 libxcb1 libxcomposite1 libxcursor1 libxdamage1 libxext6 \

libxfixes3 libxi6 libxrandr2 libxrender1 libxss1 libxtst6 ca-certificates \

fonts-liberation libappindicator1 libnss3 lsb-release xdg-utils wget curl

rm -r /var/lib/apt/lists/*

cd /

git clone https://github.com/alvarcarto/url-to-pdf-api.git pdf_server

cd pdf_server

npm install

chmod -R 0755 .

And now we need to define what happens when we start an instance of the container. In this situation, we want to run the commands that starts up the url-to-pdf-api server:

%startscript

cd /pdf_server

# Use nohup and /dev/null to completely detach server process from terminal

nohup npm start > /dev/null 2>&1 < /dev/null &

Also, the server requires some variables be set, which we can do in the environment section:

%environment

NODE_ENV=development

PORT=8000

ALLOW_HTTP=true

URL=localhost

export NODE_ENV PORT ALLOW_HTTP URL

Now we can build the definition file into an image! Simply run and the image will be ready to go:

$ sudo singularity build url-to-pdf-api.img Singularity

Running the Server¶

Now that we have an image, we are ready to start an instance and run the server:

$ singularity instance.start url-to-pdf-api.img pdf

We can confirm it’s working by sending the server an http request using curl:

$ curl -o google.pdf localhost:8000/api/render?url=http://google.com

% Total % Received % Xferd Average Speed Time Time Time Current

Dload Upload Total Spent Left Speed

100 51664 100 51664 0 0 12443 0 0:00:04 0:00:04 --:--:-- 12446

If you shell into the instance, you can see the running processes:

$ singularity shell instance://pdf

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

Singularity pdf_server.img:~/bauerm97/instance-example> ps auxf

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

node 87 0.2 0.0 20364 3384 pts/0 S 16:16 0:00 /bin/bash --norc

node 88 0.0 0.0 17496 2144 pts/0 R+ 16:16 0:00 \_ ps auxf

node 1 0.0 0.0 13968 1904 ? Ss 16:10 0:00 singularity-instance: mibauer [pdf]

node 3 0.1 0.4 997452 40364 ? Sl 16:10 0:00 npm

node 13 0.0 0.0 4340 724 ? S 16:10 0:00 \_ sh -c nodemon --watch ./src -e j

node 14 0.0 0.4 1184492 37008 ? Sl 16:10 0:00 \_ node /scif/apps/pdf_server/p

node 26 0.0 0.0 4340 804 ? S 16:10 0:00 \_ sh -c node src/index.js

node 27 0.2 0.5 906108 43424 ? Sl 16:10 0:00 \_ node src/index.js

Singularity pdf_server.img:~/bauerm97/instance-example> ls

LICENSE README.md Singularity out pdf_server.img

Singularity pdf_server.img:~/bauerm97/instance-example> exit

Making it Pretty¶

%appinstall pdf_server

git clone https://github.com/alvarcarto/url-to-pdf-api.git pdf_server

cd pdf_server

npm install

chmod -R 0755 .

And update our to point to the app location:

%startscript

cd "${APPROOT_pdf_server}/pdf_server"

# Use nohup and /dev/null to completely detach server process from terminal

nohup npm start > /dev/null 2>&1 < /dev/null &

Now we want to define the pdf_client app, which we will run to send the requests to the server:

%apprun pdf_client

if [ -z "${1:-}" ]; then

echo "Usage: singularity run --app pdf <instance://name> <URL> [output file]"

exit 1

fi

curl -o "${SINGULARITY_APPDATA}/output/${2:-output.pdf}" "${URL}:${PORT}/api/render?url=${1}"

As you can see, the app checks to make sure that the user provides at least one argument. Now that we have an output directory in the container, we need to expose it to the host using a bind mount. Once we’ve rebuilt the container, make a new directory callout for the generated PDF’s to go. Now we simply start the instance like so:

$ singularity instance.start -B out/:/scif/data/pdf_client/output/ url-to-pdf-api.img pdf

And to request a pdf simply do:

$ singularity run --app pdf_client instance://pdf http://google.com google.pdf

And to confirm that it worked:

$ ls out/

google.pdf

When you are finished, use the instance.stop command to close all running instances.

$ singularity instance.stop \*

Important Notes¶

- The instances are linked with your user. So if you start an instance with sudo, that is going to go under root, and you will need to call in order to see it.

Container Checks¶

$ singularity check ubuntu.img

$ singularity check --tag default ubuntu.img

Perform checks with tag “clean”

$ singularity check --tag clean ubuntu.img

Tags and Organization¶

Currently, checks are organized by tag and security level. If you know a specific tag that you want to use, for example “docker” deploys checks for containers with Docker imported layers, you can specify the tag:

USAGE

-t/--tag tag to filter checks. default is "default"

Available: default, security, docker, clean

EXAMPLE

$ singularity check --tag docker ubuntu.img

If you want to run checks associated with a different security level, you can specify with , , or :

USAGE: singularity [...] check [exec options...] <container path>

This command will run security checks for an image.

Note that some checks require sudo.

-l/--low Specify low threshold (all checks, default)

-m/--med Perform medium and high checks

-h/--high Perform only checks at level high

Note that some checks will require sudo, and you will be alerted if this is the case and you didn’t use it. Finally, if you want to run all default checks, just don’t specify a tag or level.

What checks are available?¶

Currently, you can view all installable checks here, and we anticipate adding an ability to view tags that are available, along with your own custom checks. You should also ask your administration if new checks have been added not supported by Singularity. If you want to request adding a new check, please tell us!.

Environment and Metadata¶

Singularity containers support environment variables and labels that you can add to your container during the build process. This page details general information about defining environments and labels. If you are looking for specific environment variables for build time, see build environment.

Environment¶

If you build a container from Singularity Hub or Docker Hub, the environment will be included with the container at build time. You can also define custom environment variables in your Recipe file like so:

Bootstrap: shub

From: vsoch/hello-world

%environment

VARIABLE_NAME=VARIABLE_VALUE

export VARIABLE_NAME

%post

echo 'export VARIABLE_NAME=VARIABLE_VALUE' >>$SINGULARITY_ENVIRONMENT

$ SINGULARITYENV_HELLO=WORLD singularity exec --cleanenv centos7.img env

HELLO=WORLD

LD_LIBRARY_PATH=:/usr/local/lib:/usr/local/lib64

SINGULARITY_NAME=test.img

PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin

PWD=/home/gmk/git/singularity

LANG=en_US.UTF-8

SHLVL=0

SINGULARITY_INIT=1

SINGULARITY_CONTAINER=test.img

- to prepend directories to the beginning of the

- to append directories to the end of the

- to override the within the container

Labels¶

$ singularity inspect dino.img

{

"org.label-schema.usage.singularity.deffile.bootstrap": "docker",

"MAINTAINER": "Vanessasaurus",

"org.label-schema.usage.singularity.deffile": "Singularity.help",

"org.label-schema.usage": "/.singularity.d/runscript.help",

"org.label-schema.schema-version": "1.0",

"org.label-schema.usage.singularity.deffile.from": "ubuntu:latest",

"org.label-schema.build-date": "2017-07-28T22:59:17-04:00",

"org.label-schema.usage.singularity.runscript.help": "/.singularity.d/runscript.help",

"org.label-schema.usage.singularity.version": "2.3.1-add/label-schema.g00f040f",

"org.label-schema.build-size": "715MB"

}

You will notice that the one label doesn’t belong to the label schema, . This was a user provided label during bootstrap. Finally, for Singularity versions >= 2.4, the image build size is added as a label, , and the label schema is used throughout. For versions earlier than 2.4, containers did not use the label schema, and looked like this:

singularity exec centos7.img cat /.singularity.d/labels.json

{ "name":

"CentOS Base Image",

"build-date": "20170315",

"vendor": "CentOS",

"license": "GPLv2"

}

You can add custom labels to your container in a bootstrap file:

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu: latest

%labels

AUTHOR Vanessasaur

The command is useful for viewing labels and other container meta-data.

Container Metadata¶

Inside of the container, metadata is stored in the directory. You probably shouldn’t edit any of these files directly but it may be helpful to know where they are and what they do:

/.singularity.d/

├── actions

│ ├── exec

│ ├── run

│ ├── shell

│ ├── start

│ └── test

├── env

│ ├── 01-base.sh

│ ├── 90-environment.sh

│ ├── 95-apps.sh

│ └── 99-base.sh

├── labels.json

├── libs

├── runscript

├── Singularity

└── startscript

- actions: This directory contains helper scripts to allow the container to carry out the action commands.

- env: All *.sh files in this directory are sourced in alpha-numeric order when the container is initiated. For legacy purposes there is a symbolic link called that points to .

- labels.json: The json file that stores a containers labels described above.

- libs: At runtime the user may request some host-system libraries to be mapped into the container (with the option for example). If so, this is their destination.

- runscript: The commands in this file will be executed when the container is invoked with the command or called as an executable. For legacy purposes there is a symbolic link called that points to this file

- Singularity: This is the Recipe file that was used to generate the container. If more than 1 Recipe file was used to generate the container additional Singularity files will appear in numeric order in a sub-directory called

- startscript: The commands in this file will be executed when the container is invoked with the command.

Reproducible SCI-F Apps¶

Why do we need SCI-F?¶

%post

# install dependencies 1

# install software A (foo)

# install software B (bar)

# install software C (foo)

# install software D (bar)

The creator may know that A and C were installed for and B and D for , but down the road, when someone discovers the container, if they can find the software at all, the intention of the container creator would be lost. As many are now, containers without any form of internal organization and predictability are black boxes. We don’t know if some software installed to , or to , or to their custom favorite folder . We could assume that the creator added important software to the path and look in these locations, but that approach is still akin to fishing in a swamp. We might only hope that the container’s main function, the Singularity runscript, is enough to make the container perform as intended.

%runscript

if some logic to choose foo:

check arguments for foo

run foo

else if some logic to choose bar:

run bar

and maybe your environment looks like this:

%environment

BEST_GUY=foo

export BEST_GUY

%environment

BEST_GUY=foo

BEST_GUY=bar

export BEST_GUY

- You have to do a lot of manual work to expose the different software to the user via a custom runscript (and be a generally decent programmer).

- All software must share the same metadata, environment, and labels.

Under these conditions, containers are at best block boxes with unclear delineation between software provided, and only one context of running anything. The container creator shouldn’t need to spend inordinate amounts of time writing custom runscripts to support multiple functions and inputs. Each of and should be easy to define, and have its own runscript, environment, labels, tests and help section.

SCI-F Apps make and transparent, and solve this problem of mixed up modules. Our simple issue of mixed up modules could be solved if we could do this:

Bootstrap:docker

From: ubuntu:16.04

%appenv foo

BEST_GUY=foo

export BEST_GUY

%appenv bar

BEST_GUY=bar

export BEST_GUY

%apprun foo

echo The best guy is $BEST_GUY

%apprun bar

echo The best guy is $BEST_GUY

Generate the container

$ sudo singularity build foobar.simg Singularity

and run it in the context of and then

$ singularity run --app bar foobar.simg

The best guy is bar

$ singularity run --app foo foobar.simg

The best guy is foo

Using SCI-F apps, a user can easily discover both and without knowing anything about the container:

singularity apps foobar.simg

bar

foo

singularity inspect --app foo foobar.simg

{

"SCIF_APP_NAME": "foo",

"SCIF_APP_SIZE": "1MB"

}

What is going on, under the hood? Just a simple, clean organization that is tied to a set of sections in the build recipe relevant to each app. For example, I can specify custom install procedures (and they are relevant to each app’s specific base defined under ), labels, tests, and help sections. Before I tell you about the sections, I’ll briefly show you what the organization looks like, for each app:

/scif/apps/

foo/

bin/

lib/

scif/

runscript.help

runscript

env/

01-base.sh

90-environment.sh

bar/

....

If you are familiar with Singularity, the above will look very familiar. It mirrors the Singularity (main container) metadata folder, except instead of we have . The name and base is chosen intentionally to be something short, and likely to be unique. On the level of organization and metadata, these internal apps are like little containers! Are you worried that you need to remember all this path nonsense? Don’t worry, you don’t. You can just use environment variables in your runscripts, etc. Here we are looking at the environment active for lolcat:

singularity exec --app foo foobar.simg env | grep foo

Let’s talk about the output of the above in sections, you will notice some interesting things! First, notice that the app’s has been added to the path, and it’s added to the . This means that anything you drop in either will automatically be added. You don’t need to make these folders either, they are created for you.

LD_LIBRARY_PATH=/scif/apps/foo/lib::/.singularity.d/libs

PATH=/scif/apps/foo/bin:/scif/apps/foo:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin

Next, notice that we have environment variables relevant to the active app’s (foo) data and metadata. They look like this:

SCIF_APPOUTPUT=/scif/data/foo/output

SCIF_APPDATA=/scif/data/foo

SCIF_APPINPUT=/scif/data/foo/input

SCIF_APPMETA=/scif/apps/foo/scif

SCIF_APPROOT=/scif/apps/foo

SCIF_APPNAME=foo

We also have foo’s environment variables defined under , and importantly, we don’t see bar’s.

BEST_GUY=foo

Also provided are more global paths for data and apps:

SCIF_APPS=/scif/apps

SCIF_DATA=/scif/data

%appfiles foo

runfoo.sh bin/runfoo.sh

and then maybe for install I’d make it executable

%appinstall foo

chmod u+x bin/runfoo.sh

You don’t even need files! You could just do this.

%appinstall foo

echo 'echo "Hello Foo."' >> bin/runfoo.sh

chmod u+x bin/runfoo.sh

We can summarize these observations about using apps:

- the specific environment () is active because is foo

- the lib folder in foo’s base is added to the LD_LIBRARY_PATH

- the bin folder is added to the path

- locations for input, output, and general data are exposed. It’s up to you how you use these, but you can predictably know that a well made app will look for inputs and outputs in it’s specific folder.

- environment variables are provided for the app’s root, it’s data, and it’s name

I didn’t show you the complete output of a to the environment when running foo in the first example - because the remainder of variables are more fit for a discussion about app interaction. Essentially, when any app is active, we also have named variable that can explicitly reference the environment file, labels file, runscript, and folders for all app’s in the container. For our above Singularity Recipe, we would also find:

SCIF_APPDATA_bar=/scif/data/bar

SCIF_APPRUN_bar=/scif/apps/bar/scif/runscript

SCIF_APPROOT_bar=/scif/apps/bar

SCIF_APPLIB_bar=/scif/apps/bar/lib

SCIF_APPMETA_bar=/scif/apps/bar/scif

SCIF_APPBIN_bar=/scif/apps/bar/bin

SCIF_APPENV_bar=/scif/apps/bar/scif/env/90-environment.sh

SCIF_APPLABELS_bar=/scif/apps/bar/scif/labels.json

SCIF_APPENV_foo=/scif/apps/foo/scif/env/90-environment.sh

SCIF_APPLABELS_foo=/scif/apps/foo/scif/labels.json

SCIF_APPDATA_foo=/scif/data/foo

SCIF_APPRUN_foo=/scif/apps/foo/scif/runscript

SCIF_APPROOT_foo=/scif/apps/foo

SCIF_APPLIB_foo=/scif/apps/foo/lib

SCIF_APPMETA_foo=/scif/apps/foo/scif

SCIF_APPBIN_foo=/scif/apps/foo/bin

This is really great because it means that we can have apps interact with one another internally. For example, let’s modify the recipe a bit:

Bootstrap:docker

From: ubuntu:16.04

%appenv cow

ANIMAL=COW

NOISE=moo

export ANIMAL NOISE

%appenv bird

NOISE=tweet

ANIMAL=BIRD

export ANIMAL

%apprun moo

echo The ${ANIMAL} goes ${NOISE}

%appenv moo

. ${APPENV_cow}

In the above example, we have three apps. One for a cow, one for a bird, and a third that depends on the cow. We can’t define global functions or environment variables (in or , respectively) because they would interfere with the third app, bird, that has equivalently named variables. What we do then, is source the environment for “cow” in the environment for “moo” and the result is what we would want:

$ singularity run --app moo /tmp/one.simg

The COW goes moo

- **SCIF_APPBIN_*: the path to the bin folder, if you want to add an app that isn’t active to your ‘PATH‘

- **SCIF_APPLIB_*: the path to the lib folder, if you want to add an app that isn’t active to your ‘LD_LIBRARY_PATH‘

- **SCIF_APPRUN_*: the app’s runscript (so you can call it from elsewhere)

- **SCIF_APPMETA_*: the path to the metadata folder for the app

- **SCIF_APPENV_*: the path to the primary environment file (for sourcing) if it exists

- **SCIF_APPROOT_*: the app’s install folder

- **SCIF_APPDATA_*: the app’s data folder

- **SCIF_APPLABELS_*: The path to the label.json in the metadata folder, if it exists

Singularity containers are already reproducible in that they package dependencies. This basic format adds to that by making the software inside of them modular, predictable, and programmatically accessible. We can say confidently that some set of steps, labels, or variables in the runscript is associated with a particular action of the container. We can better reveal how dependencies relate to each step in a scientific workflow. Making containers is not easy. When a scientist starts to write a recipe for his set of tools, he probably doesn’t know where to put it, perhaps that a help file should exist, or that metadata about the software should be served by the container. If container generation software made it easy to organize and capture container content automatically, we would easily meet these goals of internal modularity and consistency, and generate containers that easily integrate with external hosts, data, and other containers. These are essential components for (ultimately) optimizing the way we develop, understand, and execute our scientific containers.

Cowsay Container¶

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/singularityware/singularity/master/examples/apps/Singularity.cowsay

sudo singularity build moo.simg Singularity.cowsay

What apps are installed?

singularity apps moo.simg

cowsay

fortune

lolcat

Ask for help for a specific app!

singularity help --app fortune moo.simg

fortune is the best app

for app in $(singularity apps moo.simg)

do

singularity help --app $app moo.simg

done

cowsay is the best app

fortune is the best app

lolcat is the best app

singularity run --app fortune moo.simg

My dear People.

My dear Bagginses and Boffins, and my dear Tooks and Brandybucks,

and Grubbs, and Chubbs, and Burrowses, and Hornblowers, and Bolgers,

Bracegirdles, Goodbodies, Brockhouses and Proudfoots. Also my good

Sackville Bagginses that I welcome back at last to Bag End. Today is my

one hundred and eleventh birthday: I am eleventy-one today!"

-- J. R. R. Tolkien

singularity run --app fortune moo.simg | singularity run --app lolcat moo.simg

You will be surrounded by luxury.

This one might be easier to see - pipe the same fortune into the cowsay app:

singularity run --app fortune moo.simg | singularity run --app cowsay moo.simg

________________________________________

/ Executive ability is prominent in your \

\ make-up. /

----------------------------------------

\ ^__^

\ (oo)\_______

(__)\ )\/\

||----w |

|| ||

and the final shabang - do the same, but make it colored. Let’s even get lazy and use an environment variable for the command:

CMD="singularity run --app"

$CMD fortune moo.simg | $CMD cowsay moo.simg | $CMD lolcat moo.simg

_________________________________________

/ Ships are safe in harbor, but they were \

\ never meant to stay there. /

-----------------------------------------

\ ^__^

\ (oo)\_______

(__)\ )\/\

||----w |

|| ||

Yes, you need to watch the asciinema to see the colors. Finally, inspect an app:

singularity inspect --app fortune moo.simg

{

"SCIF_APP_NAME": "fortune",

"SCIF_APP_SIZE": "1MB"

}

Singularity and Docker¶

Singularity is good friends with Docker. The reason is because the developers use and really like using Docker, and scientists have already put much resources into creating Docker images. Thus, one of our early goals was to support Docker. What can you do?

- You don’t need Docker installed

- You can shell into a Singularity-ized Docker image

- You can run a Docker image instantly as a Singularity image